Like his earlier work, it concentrates on the sights and sounds of backroads America, but it places those images in a different and disturbing context.

"Landscape Suicides" is centered on two murder cases: the story of Bernadette Protti, a teenager who stabbed a high school classmate to death in a California suburb in 1984, and the story of Ed Gein, a Wisconsin farmer who killed and grotesquely mutilated a number of victims in the late 1950s.

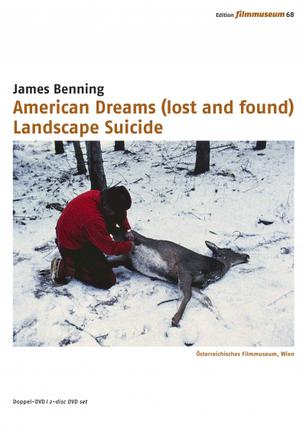

Each half of the film follows the same structure: the camera, looking through the windshield of a moving car, crosses the locales where the crimes took place (in California, it is spring and it is raining; in Wisconsin, it is winter and snow is falling); an actor, playing the killer, reads excerpts from the court records while the camera looks on impassively (Rhonda Bell plays Protti, Elion Sacker appears as Gein); and finally the camera returns to the landscape, as Benning strings together static, wide-angle shots of streets and buildings, fields and hills, that emphasize a perfect calm and an awful immensity of space. The shift, from moving to still camera, has been made through the medium of the killer--the film is a movement toward death.

Both these cases have obvious cinematic references: The Protti case, with its cheerleader victim and placid suburban setting, could be the stuff of any of several dozen teen slasher films, from "Halloween" on; the Gein case directly inspired "Psycho," as well as "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre" and any number of lesser exploitation movies.

It's part of Benning's project in "Landscape Suicide" to reclaim these deaths from the realm of popular fiction and place them again in a real world. His method is, alternatively, both to refuse to look (the killings, made familiar and even banal by their endless cinematic representation, are not depicted) and to look harder than anyone else.

Looking straight into the murderers' faces, as they describe their crimes in flat, methodical terms, Benning evokes the tremendous pain of a teenager disliked because she was "different," as well as the pathetic helplessness of Gein, trapped by forces beyond his control or consciousness. The pain of the victims is evoked, too, in extended shots that show a 1984 teenager talking animatedly on her bedroom phone while a song from "Cats" plays on the soundtrack, and a 1957 housewife dancing by herself to Patsy Cline's "Tennessee Waltz."

But Benning's deepest interest lies in the way the crimes have imprinted themselves on the landscape, and the no less powerful way the landscapes have imprinted themselves on the crimes. The prosperous California suburb is linked to the depressed Midwestern farm town through a shared sense of isolation, desolation and quiet despair.

We finally come to understand that both of these towns are located in the same place, somewhere in the dark recesses of the American Dream.